UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN

Swiss transplant Barbara Widmer has put down strong roots at Brancaia in the Chianti hills, where she aims to create wines that are an original expression of the local terroir. Nargess Banks visits the estate

Barbara Widmer wasn’t born into a wine dynasty. Quite the contrary. The Swiss native was heading towards a career in architecture when, one harvest, her destiny took a turn as she swapped Zurich city life for the Tuscan hills. Now, 34 years on, as CEO and winemaker at Brancaia, she leads a team who craft a measured portfolio of wines that are structured and elegant, and are an original expression of her estate.

For Widmer, winemaking is a philosophy – one that is in constant appraisal. She mentions this quite a few times during our conversations, and the Brancaia website is clear about this ethos: “Every vintage, every floor, every idea that is realized is a new beginning, a new attempt to raise the quality level even further.”

Brancaia’s quest to improve each vintage is methodical. It involves exploring clones from indigenous and international vines, and experimenting with different cultivation and fermentation methods. This means working with both traditional and modern vinification practices, aging the wine in wooden barrels of various sizes, as well as cement and steel tanks. In short, for Brancaia winemaking is a never-ending process of discovery.

And you sense this intellectual approach, as well as a respect for detail, at every touchpoint at Brancaia. To start with, the architecture of the winery and visitor center sits perfectly in harmony with the Tuscan landscape. The menu served at Osteria Brancaia is inspired by local gastronomy and made largely with vegetables grown on the estate. The staff are friendly and informed, while the label design is clear, considered and timeless. And, as a small gesture that says so much, the website has the entire team, including the grape pickers and cleaning staff, listed by name and the number of dedicated years at Brancaia. Then there is Barbara Widmer herself: sincere, worldly and very real.

We are meeting at the main winery and visitor center in Radda, perched on the Chianti hills between Florence and Siena. “The most challenging part of being a winemaker is to be committed to what you want to do, but at the same time have an open mind,” she begins as we settle in what was once her family home – a pleasantly restored farmhouse at the foothill of the winery, overlooking a pond filled with waterlilies and a pool nestled in natural stone. Earlier we were treated to a tasting menu at the Osteria Brancaia, on the terrace with vistas of the vineyards and the lush woodlands of cypress beyond. This really is a picture-postcard spot.

Brancaia location maps and views of Casa Brancaia

A TALE OF TWO CULTURES

When the estate was purchased in 1981 by Barbara’s parents, Bruno and Brigitte Widmer, the house and land were in complete ruins. Many local Tuscans had abandoned the area after World War II, relocating to nearby towns or big cities in search of work and the new Italian dream. The Widmers’ first act was to restore the land and plant new vines, and the family would often spend summers vacationing here. Later, Barbara Widmer raised her own children at the house, in 2014 moving to another restored property at a walking distance. Now the Radda house is enjoyed by visiting family and friends.

Brancaia was more of a hobby project for the Widmers, who continued to live in Zurich, where Bruno Widmer worked as an advertising executive. In 1998 they entrusted its operations to their daughter. Under her stewardship the portfolio has grown from two reds in the Chianti Classico style, to nine wines, to include six reds, a white, a rosé and a sparkling. The wines are vinified using grapes from vineyards that are spread across the three Tuscan estates: two in Chianti Classico in the subzones of Castellina and Radda, and a third along the coastal area, bordering the Tyrrhenian sea in the Maremma. All three plots have different soil composition and benefit from micro-climates which impact greatly on the fruit.

This area of Tuscany is steeped in winemaking tradition. Brancaia is respecting history but looking ahead with Widmer acutely aware of her place in her adopted land. “Coming from another country and from a different background can be difficult but also healthy,” she says. “There is no tradition to follow yet we also feel very connected to this region and respect the tradition. I truly don’t believe we set out to do things differently. Rather, it’s about being open minded, not being stuck to some rules because of pressures. My parents are extremely open-minded people, and I hope they passed this onto me.”

It was her parents who first began teasing her about studying winemaking when she was a young adult, but at the time, she showed no interest. “I would joke saying: ‘why don’t you bother my two older brothers?’ But they never answered,” she says laughing. “I’m not one of those people who always knew what I wanted to do. We owned the winery but it was in Tuscany and I grew up in Zurich, so when I came to visit it wasn’t just coming from Switzerland to Italy but from the city to the countryside.”

Widmer went on to study architecture, but two years into the course, she became self-critical, doubting the level of professional success that she would likely master. “I knew I wouldn’t be able to realize the projects I loved and that I would have to compromise.” So, she dropped out of architecture school.

Soon after, Widmer approached her parents to discuss if wine was indeed a career for her. “If they were overjoyed, they certainly didn’t show it,” she says, sounding amused at the memory. The seed was firmly planted following a quick course in wine, and a month spent in Tuscany at harvest time. “It was the first real harvest I was witnessing and it was amazing. Seeing the fruit come to the cellar and so much going on. It was fascinating.”

Serious about a career in wine, in 1993 Widmer joined the Swiss winery Domaine des Balisier – the largest organic winery in the country, it was in the process of becoming biodynamic. Here she spent six months in the vineyard and six in the cellar. “It was a huge opportunity for me, and from the first day on I knew that this was my world.”

Widmer’s early architectural training still comes in handy as she oversees building restorations, and designs most of the furniture at the Osteria using reclaimed materials from the winery, including the unused barriques. She tells me the gardener is handy with woodwork and one of the tractor drivers is skilled with steel, so she simply sketches the designs, calculates the sizes, and the team makes it happen.

Even the bottle label design is an area she oversees. Originally her father’s branding, the unique logo (deemed rather risky when first conceived in the conservative 1980s wine scene) has been modified and refined through the years, with each new wine in the portfolio given its own color scheme to express where it sits within the family. And seeing the bottles lined up, you can sense this logic. The distinctive design also helps mark Brancaia in a crowded wine market such as Tuscany, where the designs tend to be more traditional.

Widmer also dabbles in painting – a particularly striking abstract work adorns the walls of the winery as you descend to the cellars – but she is quick to note she hasn’t painted in several years. “Painting needs time. Doing furniture is much easier,” she replies modestly.

Barbara Widmer, family and staff enjoying a Tuscan meal at Osteria Brancaia overlooking the Chianti hills in Radda, the Brancaia 'Il Blu' 2018 vintage

“Coming from another country and from a different background can be difficult but also healthy. There is no tradition to follow yet we also feel very connected to this region and respect the tradition”

GREEN GLORY

Most importantly is Brancaia’s intimate partnership with nature. This is a certified organic winery and its ethos is rooted in attentive vineyard work which, Widmer believes, has a profound impact on the quality of the fruit and its connection to the very spot in which it grows.

She says: “We see a lot of benefits not only in the grape quality, but also the vines are healthier, the soil is healthier since there is no monoculture, while the grasses and wildflowers attract insects, wildlife and birds who eat the insects. We see the vine is connected with the soil and can resist extreme weather conditions much better, while the older plants can more easily adapt and resist change. It’s about the harmony of nature.”

Although the Radda and Castellina vineyards are a short drive from one another in the Chianti region of Tuscany, the former is wilder and the surrounding forests have an impact on the climate. Meanwhile the Maremma vineyard, also in Tuscany, is hotter, dryer and a little rougher in landscape, but benefits from the breeze from the nearby sea. I’m interested to know if the place, the spot, impacts on the expression of the wines. “I honestly feel being connected to the spot is very important, no matter what the landscape,” she replies.

Since 2017, Brancaia has adapted the Massal Selection method, replanting new vineyards with cuttings from the estate’s oldest vines, some of which are now 30, from the same plot. The best vines are selected from each of the vineyards, are examined in the laboratory and undergo micro-fermentation to see if they taste as good as they look. The process is repeated over five years, with vines reproduced for all new plantings based on the selected best. Widmer says of the method: “It makes sense, as these older vines have adapted to the specific plot and their microclimates, are therefore more resilient, so that this method of replanting creates stronger vines.”

Dry farming, as in cultivating (where possible) without irrigation, is also extremely important to Widmer. “I may have to change my ways one day, but so far in Tuscany this is possible – that is if you plant the right grape variety in the right spot.” She says that even if you weren’t doing this out of ecological reasons, the quality of the grape is more interesting and the fruit links better to the terroir. “Dry farming intensifies the flavors of the grape varieties but also the flavors of the vineyard, the spot.”

Clearly passionate about the topic, she continues: “With irrigation you may give up some of the typicity of the spot. You see when you irrigate, everything matures a bit faster, so you have to pick the fruit a few days earlier as they ripen quicker. Whereas without irrigation the grapes get to stay on the vine a little longer, gaining more flavor and structure. More importantly, with irrigation the vine roots stay at the top of the soil; they don’t need to dig deep down and therefore won’t be so linked to the soil.”

Widmer knows the most compelling wines will bear the true hallmark of the terroir. “I truly believe the focus of a winery should not only be on making outstanding wines, but in creating unique wines expressing the character of the terroir. And the one thing I can do is to link Brancaia wines to our vineyards, connect them to the soil. No one else can produce the same wines. They are unique to this place.”

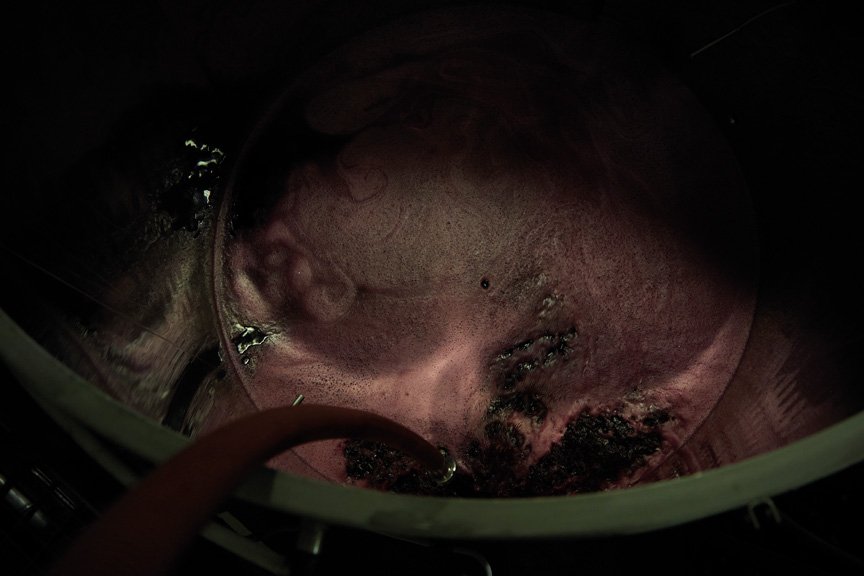

Brancaia’s quest to improve each vintage is methodical and involves working and aging the wine in wooden barrels

of various sizes, as well as cement and steel tanks

DOWN UNDER

Earlier, we took a tour of the cellar with hospitality manager Guido Carli, who explained how fermentation and aging at Brancaia follow a highly methodological approach. Harvest, fermentation and aging take place in a simple three-tier process on three levels so the grapes and wine are transported more easily, helped by gravity. The Radda and Castellina vineyards share a single cellar at Radda, while the Maremma estate has its own cellar, with produce from all three then sent to a logistics center on the outskirts of Siena.

The grapes are picked by hand, and each plot is harvested separately, with every vineyard undergoing natural or spontaneous fermentation separately to allow the grapes to reach their optimum quality and gain a sense of typicity. The fermentation process takes typically 16 days for the lighter press, rising to 28 days for the heavier wines like Il Blu and Ilatraia.

Three different vessel types are used for aging: stainless steel, concrete vats and French oak barrels – barriques of 225,500 and 750 liters. Since each plot is vinified separately, every barrel will contain a single vineyard. Crucially, to ensure the liquid to wood contract is precisely controlled, the aging process will not exceed 18 months, and the barrels don’t go beyond the second passage, after which they are sold to other producers.

Talking with Widmer I sense the cellar work is the most creative aspect of her job as a winemaker. “Yes absolutely. In the cellar we want to maintain the typicity with each plot.” This also means not adding any purchased yeast, instead, the yeast is naturally cultivated from the vineyard, a practice Brancaia has committed to since 2008.

Widmer explains: “The composition of the flora is quite different in a cooler and rainier vintage than dryer ones, so they adapt to nature and will therefore adapt better than a bought yeast when in the cellar. We also feel this method further adds to the typicity of our vintages. We want to make outstanding wine with a maximum link to where we are. I do think winemaking at the higher level is more philosophy than science. Nothing we do can be reproduced. Each vintage is unique.”

As we begin to sample the wines, Widmer says: “When I came to the winery it was all about Tuscany IGT rules, but the rules changed and I changed. Winemaking is an evolution and, good or bad, it’s never over. You know we don’t stop dreaming until we pick the grape – after then we stop dreaming,” she clarifies. “You can’t do too much in the vineyards but you can in the cellar. In the cellar you have to accept what the grape is, understand and follow it the best you can, but not do too much. It’s a fine balance.”

“The most challenging part of being a winemaker is to be committed to what you want to do, but at the same time have an open mind”

HOSPITALITY MANAGER GUIDO CARLI AT THE VISITOR CENTRE

MARCO MARCHI WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR VITICULTURE IN MAREMMA, THRIVING BRANCAIA VINES, A VIEW OVER THE CERTIFIED ORGANIC BRANCAIA WINERY

IN A GOOD YEAR

We have spent the best part of the day at Brancaia. The bright Tuscan sun is mellowing, and with it comes a soft breeze and a veil of golden light across the vineyards, olive groves and beyond. As we stroll back towards Osteria Brancaia, I ask Widmer what it is she’s most proud of. “Oh, that’s a hard question,” she muses. “My parents’ hobby has become a real business – something that the next generation, if they want it and have the passion, can continue.” She is referring not only to her son and daughter, but also her nieces and nephews as Brancaia remains a family affair, with both her brothers involved in the business. “I’m aware that I am privileged to have had parents who have encouraged me to follow my passion and have given me Brancaia.” Looking ahead, Widmer has purchased a further plot in Radda and is dealing with something new in the Maremma but doesn’t elaborate further other than say she cannot predict if these new spots will help create new wines or if the grapes will feed into the current portfolio. “I like to let the future grow naturally.”

As we say goodbye, I ask Widmer what her 20-year-old self would think of her now. After a moment’s contemplation, she smiles a big, wide smile: “I would say, generally speaking, not too bad. I always wanted to work and I never saw myself staying at home. This has come true. I am happy to be a mother even though I hadn’t planned for it. My job makes me, most of the time, very happy. Some of our excellent team members have been with us from the start. It feels like a family – one unit. I feel very lucky.”

Is she glad she didn’t pursue a life in architecture? This time she’s quick to reply: “I am absolutely convinced that the decision was the right one for me. I have liberty in my job here. There are so many things to learn and it’s never boring. So, to answer your question, my 20-year-old self would say: ‘not too bad.’”

Learn more about Brancaia and the wines.

ART FAIR

The Brancaia Collection is a limited-edition label featuring six different designs exclusively applied to Tre. The idea was conceived in 2021 when, as a one-off gift to her parents Brigitte and Bruno Widmer for their 80th birthday, a young artist was commissioned to interpret the Brancaia label. The result was so impressive that the winery decided to use the design for a limited-edition run on Tre. The latest 2022 collection is the work of the Ukrainian artist Sergiy Maidukov, who was asked to design six different Brancaia labels as a series, with the single requirement that the two-square Brancaia layout must remain the same. The Kyiv-based artist’s illustration is a clever play on positive and negative spaces, featuring bold color combinations and textures. “Through the Brancaia Collection, our label becomes a canvas and platform for a young artist. An art exhibition of its own kind, so to speak, which hopefully will support many other young talents in the future,” says Widmer. “Art and great wine should be accessible to everyone, which is why we chose our award-winning wine Tre for this project. There is hardly anything better than being able to enjoy art in everyday life.”

The Brancaia Collection is a limited-edition label featuring six different designs exclusively applied to Tre

THE GALLO NERO STORY

The Gallo Nero is an image typically associated with Chianti Classico. But how did a black rooster come to be a symbol of this fabled wine, found on the neck of the bottles? Stretching the land between Florence and Siena, the Chianti Classico region was contested between the rival cities as far back as the Middle Ages. To put an end to the disputed borders, the two decided on a fair race: at the crack of dawn, horseback riders would set off from their respective cities, and wherever they met would define their borders. With the sole alarm clock of the day being a rooster, Florence chose a black rooster, while Siena’s bird was white. The Florentine rooster was fed little to ensure its hungry tummy would lead to a natural early rise, while Siena’s had allegedly been fed a rich diet in the hope that it would feel satisfied, have a great sleep and wake up energized. Alas for Siena, the hungry Florentine rooster was the first to rise, with the rider conquering much of the territory. The Gallo Nero has since become the chosen symbol of Chianti Classico.

WHERE TO EAT, AND WHERE TO STAY

Eating

Eating Perched on the hills at the main winery in Radda and with vistas over the vineyards, Osteria Brancaia serves simple yet elegant Tuscan dishes, with an artistic menu designed by chef Giovanni Palladino using herbs and vegetables grown in the gardens, as well as local, seasonal produce. Brancaia has invested heavily in the winery and experience center in the last few years. “I think experience is one of the most important aspects of a winery,” says CEO Barbara Widmer. “A decade ago, it wasn’t so easy to visit a winery, but this is all changing. It’s the best way to connect with people. If our team does a good job, the visitor is a brand ambassador for a lifetime. So much goes into what we do, and having people visit us for even an hour, gives some value to quality wine.” Book a wine tasting experience, take a tour of the winery and cellar, and sample the chef’s dishes paired with the estate’s wines.

Sleeping

There are plenty of wonderful places to stay in the Chianti region of Tuscany, but why not enjoy the Brancaia hospitality at the boutique hotel on the gentle rolling hills near Castellina, between Florence and Siena. Recently restored with love and care, the charming property is surrounded by fragrant herbs and flowers, olive trees, vineyards and fields, and with a long lake spread out at the foot of the vineyards. All guests can hear are the sound of chirping crickets and the singing birds, and the occasional rattle of a tractor in one of the nearby vineyards.

Photography ©Helen Cathcart, Roberto Fortunato, Brancaia

We recommend

BARBARA WIDMER IN CONVERSATION

Committed in her convictions about quality wine from healthy vineyards, Barbara Widmer, the owner and winemaker of the Tuscan winery Brancaia, tackles big environmental challenges one technique and one vine at a time

STAR STUDENT

As Brancaia celebrates 20 vintages of its flagship Ilatraia, Chandra Kurt visits the dynamic Tuscan winery to see how consultant Carlo Ferrini’s mentorship helped Barbara Widmer forge her own path

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

What does your bottle and label say about your winery? Abbie Moulton investigates how brands are rethinking packaging in terms of both style and substance

SUPER LEAGUE

Is it time to drop the name Super Tuscan and focus on quality? Cynthia Chaplin explores the new landscape of Italy’s most famous and prolific wine region