PLANTING SEEDS

Almudena Romero questions production and consumption with her ephemeral organic photography. Nargess Banks sits down with the Spanish artist

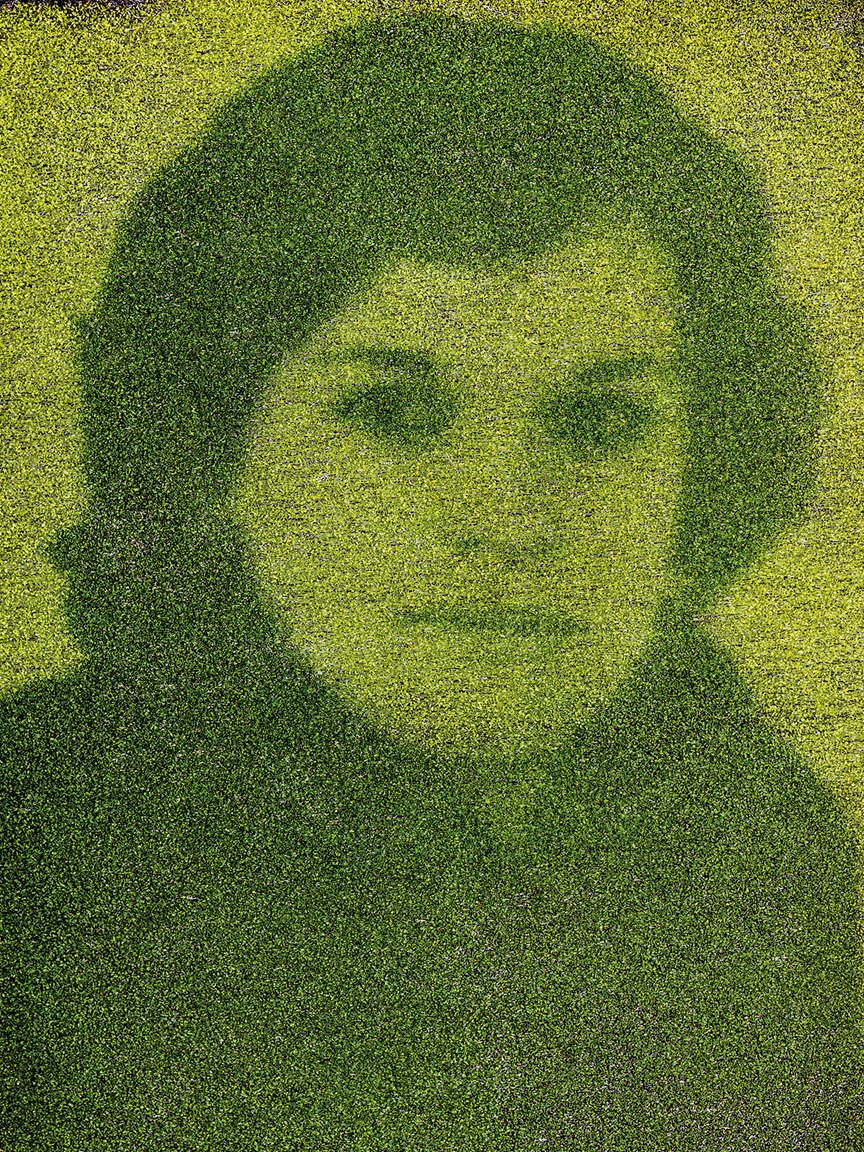

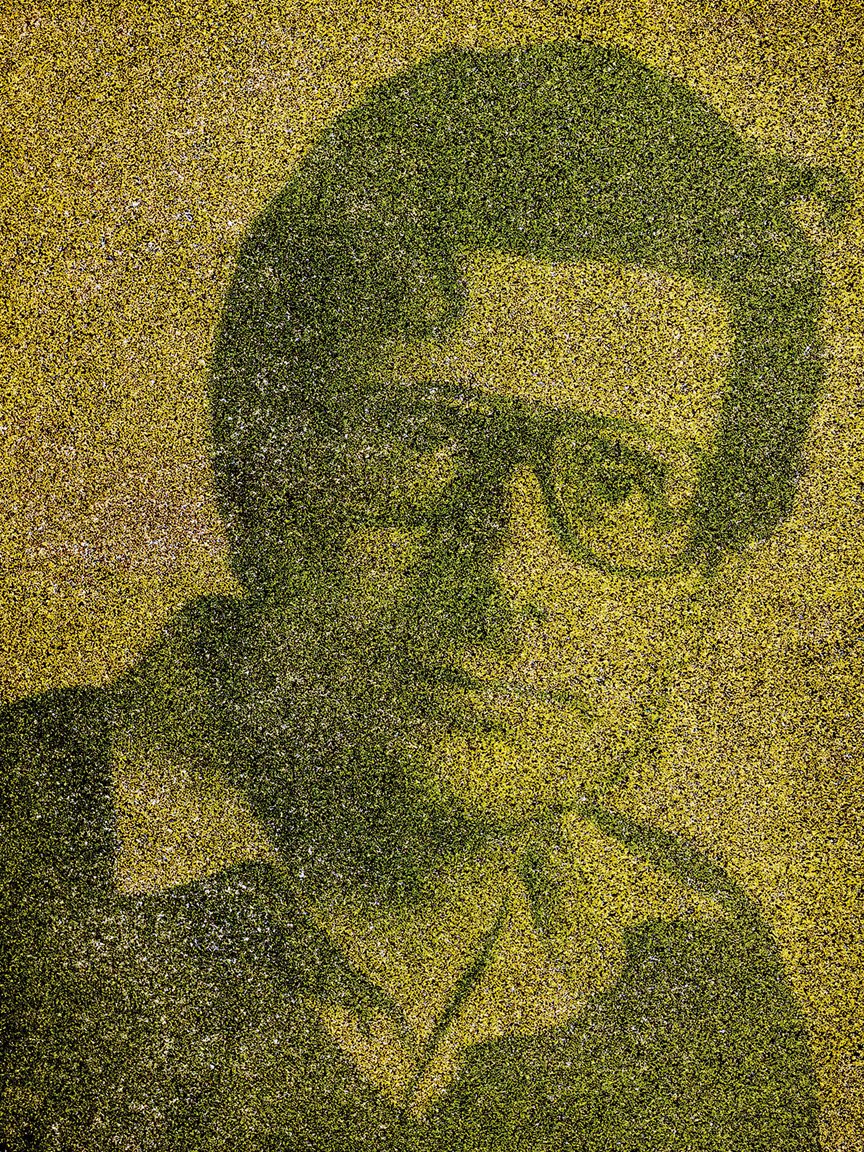

A canvas of sprouting greens reveals a fading figurative image of family. The watercress has taken only a few days to grow thanks to the nitrate-rich Spanish water used to cultivate the seeds. As the green grows, the negative projected onto the cress panels fades. Eventually, the living artwork returns to earth.

The artwork, Family Album, is part of The Pigment Change – a project by the London-based Spanish artist Almudena Romero. Her autobiographical and at times impermanent organic photographs ask the viewer to question production, consumption and ownership. Hers is a meditation on the ephemerality of life, and our relationship with nature.

The Pigment Change premiered in 2021 at Rencontres d’Arles and returned to the 2022 Paris Photo with the theme “plants as photographic artists” being further explored at a residency at the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

The artist believes in the role of art and the responsibility of the artist to help us observe and understand the world in new ways.

Top row: Almudena Romero, The Pigment Change. Chapter III: Family Album. Bottom row: Almudena Romero, The Pigment Change. Chapter I: The Act of Producing. All artwork ©Almudena Romero, collective profile ©Nicolas Jenot

What does photography mean to you?

It is a process rather than being about the result. If we start to understand photography as writing with light, then it becomes a very simple rudimentary concept that makes sense. This way it can be liberated, become more performative, more conversational.

You work directly with plants to create photographic images via photosynthesis. Can you explain your process?

I started my research on plant-based photography at my grandmother’s garden in Valencia.

I work with her plants and her nitrate-rich water to create my work, then I use my hands to project images onto the leaves. Some of the images are sharp, some not. There is a lot of invisible feminine labor that goes into growing a family and growing a garden. The fact that my hand images are not all obvious I feel is a metaphor for the invisible labor that makes the trees and plants and nature grow.

Are the layers of multiple meanings in your work intentional?

Much of my work is self-reflecting. As an artist, I want to know what’s the impact of one’s own practice, contributing to the dynamics of producing, accumulation – all of which is at the roots of the environmental issue. I want to contribute to a wider conversation as to why and where photography exists, what’s our relationship to nature, to photographic productions such as photosynthesis. A better understanding of plants can help us be more respectful to nature.

Can you speak of the ephemerality of your artwork?

In ephemerality there is hope for the future. We are facing a serious environmental crisis based on too much production, accumulation and disposal. I used to teach at the Stanford University overseas study program in Florence and I would often think of what I wanted to pass on to my students, what knowledge and skills would make sense to them in the future. This plant-based photography is part of my vision as a teacher in that these materials are ephemeral in the short run, but in the long run they are the only thing we will be able to practice. Because ephemerality is the only thing that lasts.

Artist Almudena Romero sprays her canvas of sprouting greens for Family Album at the 2020 Paris Photo

Is it a question of redefining object ownership? Perhaps the memory of an ephemeral piece of art is more valuable than possessing it as an object?

That’s a really interesting concept, this idea that because the piece is ephemeral it disappears. But art disappears from everyone’s eyes unless you own it. As an artist I’m interested in contributing to the wider conversation, helping change our understanding of the photographic medium, of our own lives and our relation to nature, rather than decorating someone’s house.

That’s quite a radical statement.

We have to review property and ownership. This is part of the problem. “Me and mine” are the dynamics of the ego. It extends to “my perspectives.” This is why I’m very keen on collaboration and on passing my knowledge and processes to my students, as I think it’s rewarding to pass on your knowledge and see it grow elsewhere and without the need to be the master of the original idea. I feel the art world needs to move more towards this direction.

Looking back, do you think “The Pigment Change” represents an important perspective shift in your artwork?

Absolutely, before this project I used plants as photographic material and objects of analysis. I would cut leaves or blend plants to use as photosensitive emulsion. For the first time

I began working with living plants, exploring the relationship between photography and performance, and with the plant as the performer. I thought I would develop a new artistic language, but instead I acquired a whole new understanding of the work and of my practice.

How do you see these ideas further evolving at your new residency?

The Pigment Change has led me to see plants not as a subject and object of the work but rather as the makers, the embodiment. It has led me to rethink our human relations to plants.

My transformative journey towards non-anthropocentrism began with The Pigment Change. So it seems the change happened in both, the plant and me.

We recommend

NEW WAYS OF SEEING

Can photography and image making alter the way we see the world and open our eyes to new possibilities? Tom Seymour visits two shows to see how artists are using their lens for positive change

FIELD NOTES

MJ Towler meets underground music producer and Riesling aficionado Skinny Pablo to see how his debut vinyl album Paris Mosel brings wine and terroir into play

BRIGHT WINES, BIG CITY

Jordan Mackay meets Jay McInerney for dinner to retrace his journey from literary sensation to leading wine columnist, sampling some fine bottles along the way

THE ARCHITECTURE OF WINERIES

Can architecture fundamentally alter our wine experience? Some of the world’s finest wineries believe that building design can, as Jonathan Bell takes a tour