THE ARCHITECTURE OF WINE

Can architecture fundamentally alter our wine experience? Some of the world’s finest wineries believe that building design can, as Jonathan Bell takes a tour

The winery rapidly became one of the most expressive typologies in modern architecture, thanks to open client briefs that celebrated the mix of function and inner workings, while simultaneously encouraging a direct visual and physical contact to the surrounding landscape.

A dramatic shimmering structure rising up above serried rows of vines has become a visual shorthand for the contemporary wine industry; aside from the label, winery architecture is an insight into the aesthetic aspirations of the winemaker.

The first wave of “starchitecture” in the late 90s and early noughties proved to be a prime for winery design. The winery rapidly became one of the most expressive typologies in modern architecture, thanks to open client briefs that celebrated the mix of function and inner workings, while simultaneously encouraging a direct visual and physical contact to the surrounding landscape. Finally, there was the growing economic need for wineries to become destinations, places that were memorable, intriguing and with the building design, a focus of attention.

Nearly 25 years after completion, the gabion walls of Herzog & de Meuron’s Dominus Winery in Napa Valley have aged to perfection, tying the building into the fertile soil of the surrounding vineyards. In Spain, Frank Gehry’s characteristically audacious structure for the award-winning Marqués de Riscal vineyard still takes the breath away; a cascading flutter of rose-colored steel, it was inspired by the curls of foil discarded with a flourish en route to uncorking.

Santiago Calatrava’s Bodegas Ysios, in the heart of Spain’s Rioja country, is another architecturally driven project. Completed in 2001, the rippling structure is one of Calatrava’s most successful, benefiting from the minimal functional requirements of a winery building. A site-specific winery, the design mirrors the Sierra Cantabria mountains that serve as a backdrop.

Swooping, dynamic forms also defined Christian de Portzamparc’s Château Cheval Blanc in Saint-Émilion, France, a 2011 winery that is an addition to the historic château and celebrates perfectly cast concrete. Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, the late Zaha Hadid and more are all represented in this typological niche: in the era of the starchitect and the age of designer as icon, every internationally renowned architect had a winery in their portfolio.

The world of architecture and wine revealed itself to be a hitherto unimaged landscape of innovation, intrigue and experimentation. The relationship between wine and design blossomed due to vineyards’ desire to signal their existence to the world, transforming historic agricultural buildings into cultural destinations in their own right. Tasting rooms, retail, restaurants, viewing galleries and even hotels were tacked on to the list of winery functions, while the fundamental requirements of winemaking were simple enough to let the architectural imagination run riot.

NEW IDEALS

As palates and preferences have become more sophisticated, architecture has also started to express key values like sustainability and environmental performance. These are, after all, buildings with a close connection to the land. Making, storing and aging wine requires precise, consistent environments, all the better for architects to explore ways to minimize the impact these structures have on their sites. As the century progressed, these structurally and sculpturally ambitious projects have given way to a more ascetic, refined style.

The architecture of wine has progressively become earthier and more authentic, with materials like rust-red Corten steel favored over the industrial high-tech of Calatrava’s aluminum roof or Gehry’s glossy steel ribbons. A good example is Smiljan Radic’s 2014 winery at Vik in Chile’s Millahue Valley. Part radical environmental experiment and part experiential playground, the underground winemaking rooms are set beneath a gently sloping open plaza that has been artfully strewn with rocks by Radic and his partner and collaborator Marcela Correa. Water runs through this landscape, providing additional cooling for the facility below, while the main hall has a broad white fabric roof, which is an elegant and lightweight way of creating shelter from the sun.

Meanwhile in Italy, Archea Associati’s remarkable Antinori Winery in Tuscany has vines planted across its broad concrete roof, with circular skylights and Corten steel walls enveloping a museum, restaurant, and auditorium. Wine is stored in underground vaults, beneath parabolic arched roofs formed from terracotta bricks, lit by the skylights.

Lately, even the starchitects are toning down their approach. Foster + Partners’ new winery for Le Dôme in Saint-Émilion had to squeeze the modern mechanics of winemaking into vineyards surrounding a medieval village, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Le Dôme is a circular, half-sunken structure that gives visitors an outlook across the vines to the old village, as well as a view down to the vats from a visitor center directly beneath the structural timber roof.

Other contemporary works that emphasize place over pomp include the Stoney Rise Cellar Door project, created by Cumulus Studio in Gravelly Beach, Tasmania. Completed in 2020, the building is domestic in scale, with a modest footprint that’s sited to provide the best views of the river running through the plot. Handmade local bricks are combined with spotted gum timber and bespoke furnishings, creating a modest structure that feels part of its context. The studio also built the structure for Devil’s Corner, a large Tasmanian vineyard run by the Australian company Brown Brothers. With its observation tower and angular light wells, Devil’s Corner is a bold local landmark.

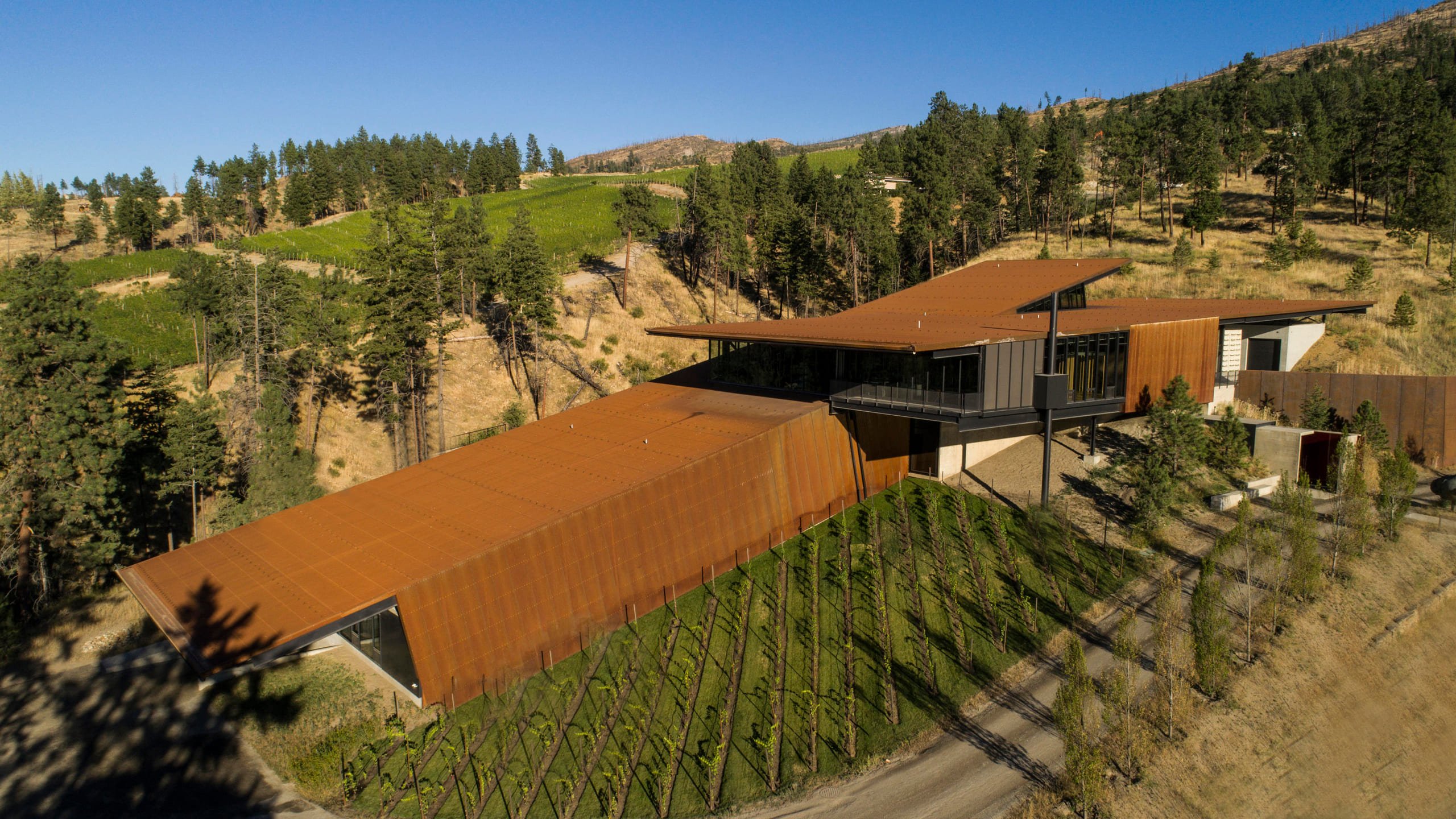

In British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, the Martin’s Lane Winery by architectural firm Olson Kundig in Kelowna is one of several vineyard projects completed by the Portland-based architects. Built for the von Mandl family, Martin’s Lane is the practice’s second project for the family. Sloped to match the terrain, the gradient of the structure helps the gentler, more natural gravity-driven winemaking process, which takes place within an enclosure formed from weathered corrugated steel sidings and rough-formed concrete.

“Martin’s Lane Winery produces wines at a superior level, and the architecture tells the story of the intersection between the land and the winemaking,” says the firm’s principal, Tom Kundig. “The building falls along the topography of the land [that produces the wine], while the hospitality portion of the program cantilevers out over the landscape, opening the space to the lake, the vineyards and the mountains beyond.”

A unique and idiosyncratic building type, the winery is a place that must blend performance with visual panache, while never straying far from the earth that sustains it. For architects, such commissions continue to be a much sought-after creative tonic.

Martin’s Lane Winery by Olson Kundig is tucked into a hillside in Kelowna, British Columbia, and draws a close parallel between the topography of the land and the gravity-flow winemaking process taking place inside. The staircase was inspired by stainless steel filtering equipment used in wine industry

The architecture of wine has become earthier and more authentic, with materials like rust-red Corten steel favored over the industrial high-tech of Calatrava’s aluminum roof or Gehry’s glossy steel ribbons.

Conceived as a rectangular form with a central daylighting fracture down the middle, Martin’s Lane’s production side follows the direction of the site, utilizing the downhill slope for its gravity flow process, while the visitor area cantilevers out above the vineyard for sweeping views of nearby Okanagan Lake

Foster + Partners’ winery for Le Dôme in Saint-Émilion squeezes the modern mechanics of winemaking into vineyards surrounding a medieval village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The relationship between wine and design blossomed due to vineyards’ desire to signal their existence to the world, transforming historic agricultural buildings into cultural destinations in their own right.

We recommend

WHERE THE ART IS

Do unusual venues and experimental curations set culture free to be explored in new and exciting ways, and by a wider public? Nargess Banks investigates

TOP TEN VINEYARDS WITH INSPIRED ART COLLECTIONS

From Château La Coste in Aix-en-Provence to the Donum Estate in Sonoma, Theodora Thomas selects the top ten vineyards with inspired art collections

UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN

Swiss transplant Barbara Widmer has put down strong roots at Brancaia in the Chianti hills, where she aims to create wines that are an original expression of the local terroir. Nargess Banks visits the estate

PLANTING SEEDS

Almudena Romero questions production and consumption with her ephemeral organic photography. Nargess Banks sits down with the Spanish artist