RIOJA REBORN

A band of forward-thinking winemakers is breathing new life into the Spanish wine industry, with grand plans to celebrate local terroir and excellency, as Brett Davis investigates

Like most fine dining sommeliers in the US, I always had go-to bottles on my wine list to help transition the typical California wine drinker to wines from the Old World – European wines that would better pair with the style of food on the restaurant’s menu. And since I was based in Louisville, Kentucky, I often had a much more difficult task, in that I needed to convert Bourbon drinkers (even if just for the one evening) to a wine that would enhance their dining experience. A Rioja Reserva or Gran Reserva inevitably became my huckleberry since they would offer the familiar aromas of vanilla, dill, coconut and sweet dried fruit that only extended American oak aging can provide.

As Bourbon is to American whiskey, Rioja is to Spanish wine when it comes to its fame, and the countless origin stories. Every producer, distributor and writer seems to have their own twist and tale. To add to the complexity, a large percentage of the internationally distributed Rioja brands, and the gallons behind them, are produced by a small number of large industrial wineries. What’s more, it is a rare individual who can tell the difference between the various brands in a blind tasting since the general flavor profiles, though delicious, are definitive in their uniformity. Is this a bad thing? Absolutely not. The consumer confidence in this consistency has contributed to Rioja’s great success.

But nothing lasts forever; tastes change and trends evolve. Today’s wine professionals are increasingly seeking out and pushing forward producers and production methods that demonstrate geographical terroir as opposed to products dominated by the characteristics of the barrels or cellars they are aged in. And, since the 1970s, Rioja wines have been defined by the time they age in wood, and with no quality classification being designated to vineyards or villages from which the grapes are grown.

While Bourbon is safe for the foreseeable future, Rioja is years into crisis mode with declining reputation, demand and value across the board, and is now generally thought of as a grocery store product. With but just a few exceptions, this has made it difficult for artisan Rioja producers to find success in the top restaurants and wine shops (even in Spain).

It has driven the value of Rioja grapes so low that it’s becoming unsustainable for the growers that supply the larger wineries. Predictably, steep hillside and hard-to-reach higher elevation vineyards have often been abandoned in favor of vineyards located in the flatter areas that are easier to maintain and harvest. Driving through Rioja recently, I was stunned to see hundreds of abandoned terraced vineyards hillside

after hillside.

Winemakers Telmo Rodríguez and Pablo Eguzkiza at their Lanzaga vineyards, located to the south of Bilbao in northern Spain

ENTER THE MATADOR

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a small group of Spanish wineries started to emerge producing wines with flavor profiles and winemaking sensibilities more akin to the greatest wines of France than their regional peers. The producers made single vineyard expressions and revived forgotten indigenous varietals. In the winery, some used French oak in lieu of the traditional American oak, while others chose to impart very little oak influence at all. Their distinctiveness and quality standards made them all outliers within their own appellations. Even though the demand and prices rose for many of these producers, their true potential marketplace value remained limited due to the global reputation of the wines from both Spain and their individual DOs.

One of the most respected voices of this Spanish terroir-driven movement is Rioja producer Telmo Rodríguez. His family’s Remelluri estate started producing a single vineyard Rioja wine in the early 1970s. Today, Rodríguez’s mission, along with his winemaker partner Pablo Eguzkiza, is to locate and revive abandoned vineyards with “grand cru” potential throughout Spain.

In Rioja, Bodega Lanzaga is the avenue for this mission. The estate has two separate winemaking facilities with distinct purposes. Lanzaga’s main modern facility is focused on the village expression wines, whereas the small hundred-year-old cellar, hidden in Haro, is used for the old vine single cru bottlings. Rodríguez and Eguzkiza have also revived grand cru-worthy sites inside the Valdeorras DO in Galicia and in the Sierra de Gredos DO in Castilla y León, and they are helping to reawaken these almost forgotten appellations.

I first met Rodríguez while hosting a group of Miami-based sommeliers to taste and discuss the wines of Lanzaga. Everyone at the table agreed that the fresh fruit profile and living earth terroir of his wines were a welcome reprieve from the usual Rioja profile most consumers are accustomed to.

Somms being somms, without fail at least one person asked about the precise varietal breakdown for every wine we tasted, and each time Rodríguez graciously deflected the dialogue away from specific grapes to what the sum of each site provides on a particular vintage. He made it very clear that we should not lose sight of the vineyard in favor of the vines.

In 2016 at the Club Matador in Madrid, Rodríguez hosted a large group of wine professionals for a round table discussion about the future of the Spanish wine industry. Participants included other quality-driven winemakers as well as journalists, critics and tradespeople. This gathering led to a manifesto that gained the signatures of over 200 highly respected Spanish wine producers.

This “Matador Manifesto” became an ultimatum-free plea to the Regulatory Boards of Spanish wine regions to consider a pyramid quality classification system for vineyards within their regions, similar to what is found in the highest regarded appellations in Europe. The last paragraph of the manifesto pretty much sums it up:

“Therefore, we call upon the Regulatory Boards to be sensitive to the new wine reality that is emerging all over Spain and to approach a classification of the land in terms of quality. We are certain that establishing such distinctions is the first step towards excellence. Beyond emerging as an unstoppable trend, terroir wines are the best way to improve the quality of Spanish wines and achieve international recognition.”

LEADING THE WAY

The movement is a cultural change still in its infancy, and it will take time and patience to mature. It took almost 50 years for Barolo to make its single cru system official after the first vineyard designated bottlings in the early 1960s, just as it did for Germany to finalize their Grosse Gewach and Grosse Lage system. Spain is no different. Yet it seems to be evolving rapidly with Priorat’s quality system in place for Catalan wines, and Rioja allowing certain vineyards and villages to be noted on labels.

The leaders of this change have wisely chosen a non-combative path by working with their regulatory boards and effecting change from within. They are showing the best paths of change by example and proof of concept as demand continually increases for their wines internationally.

A few months after the Club Matador event, as a follow-up, Rodríguez hosted a meeting with 20 of the high-quality producers at his Remelluri estate. Three years of these meetings led to the formation of Futuro Viñador Collective, a non-profit association of terroir-driven wineries dedicated to modeling the future of the Spanish wine industry back to a time when small family-owned bodegas dominated the winemaking landscape.

By encouraging and aiding new artisan producers, rediscovering forgotten regions, restoring abandoned vineyards, and protecting traditional winemaking methods, they hope to revive the rural communities of these areas and inject life back into the small villages that are struggling to exist today. As they so eloquently put it, “Our future lies in the past.”

Brett Davis is a Master Sommelier

for Maze Row

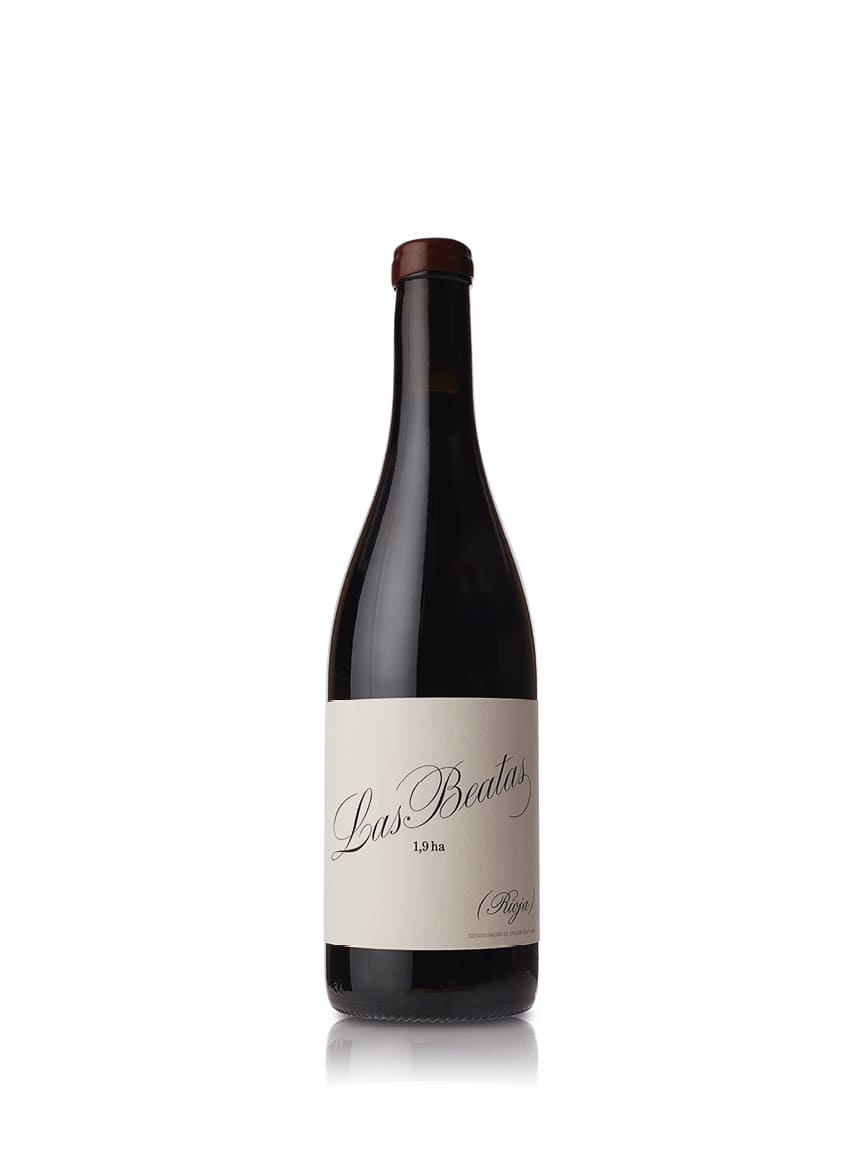

BODEGA LANZAGA RARE WINES

Las Beatas

Las Beatas is located in the village of Labastida in the most northwestern area of Rioja Alavesa with the tertiary soils of sandstone and marl. From 488 to 610 meters a.s.l, this ten-tier terraced vineyard wraps clockwise around the hillside from east to northwest facing. This old bush-trained vineyard with some newer plantings is a true field blend of eight or nine local varietals. The wines from this vineyard tend to be floral and elegant with multilayers of complexity. 1.9 ha; 1,527 bottles produced.

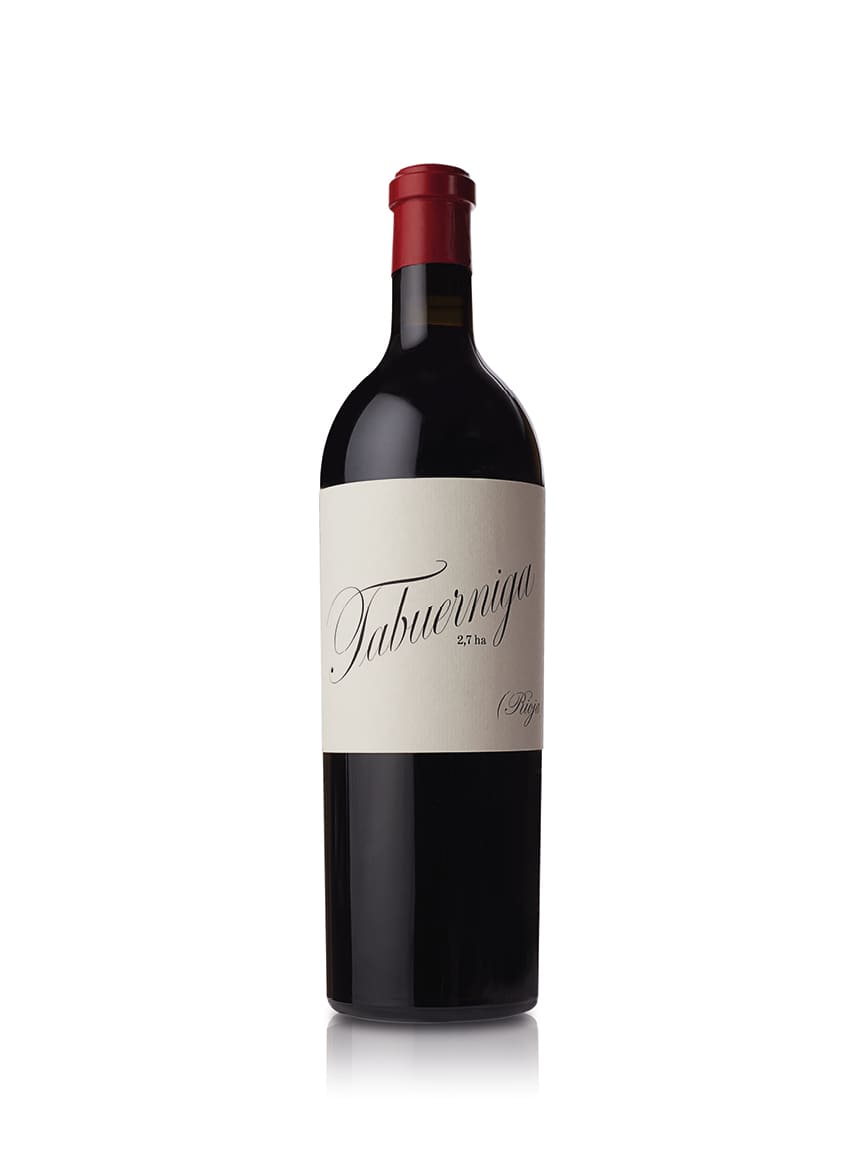

Tabuérniga

Tabuérniga is a narrow east-facing vertical vineyard just outside the village of Labastida, spanning an elevation of 518 to 640 meters a.s.l. with sandstone and marl soils. Bush-trained with a diverse varietal mixture where the shorter vegetative cycle grape varieties offer a unique expression producing sober, austere wines of depth and elegance. 2.7 ha; 3,960 bottles produced.

El Velado

El Velado is an 80-year-old vineyard located on the easternmost part of the village of Lanciego at an elevation just below 610 meters a.s.l. Made up of chalky clay soils with bush trained Tempranillo, Garnacha and other red and white indigenous varietals. Even though Tempranillo is the highest percentage of the plantings, the southwest aspect provides full sunlight exposure allowing the Garnacha to fully express itself in the wines with red juicy fruit undertones. 0.93 ha; 1,495 bottles produced.

La Estrada

La Estrada was planted in the 1940s in the western part of the village of Lanciego. One of the highest elevation vineyards in the area at above 610 meters a.s.l., this small northeast facing plot is traditional bush-trained Tempranillo and Graciano planted in pure chalk clay. Wines from here tend to be firm and rustic showing great depth and balance. 0.64 ha; 2,037 bottles produced.

Photography ©Helen Cathcart, Rob Lawson

We recommend

WINE TRAILS SPAIN: LA RIOJA

Few tourists visit the Spanish wine region, yet it makes for a unique holiday location, says Mike MacEacheran, who follows the Ebro Valley to find peace among the vineyards and wineries of historic La Rioja

REBEL WITH A CAUSE

Winemaker extraordinaire Telmo Rodríguez has helped redefine Rioja with his unique terroir-focused village wines, as Nargess Bank discovers

EXPLORE MAZE ROW’S HALO WINES

Maze Row has curated a collection of wines from unique producers, each with their own individual expression. Sommelier and Italian wine specialist John Irwin picks out the halos in the company portfolio

SOMMELIERS ARE USING THEIR CRAFT TO OPEN OUR PALATES

Sommeliers and wine educators can open our eyes to new ways of experiencing wine through artistically curated programs that tap into the mind and soul. We speak to a diverse group doing just that