RATTI’S HERO

His father Renato put Barolo on the map. Now Pietro Ratti is transforming the revered wine for new generations. Nargess Banks meets the vintner at his Piedmont vineyard

“I feel deeply connected to this land. You see, with wine, you get the transformation of land into taste. With wine, you can really understand the sense of a place. There are few products that can do this,” says Pietro Ratti, owner of the eponymous winery and the son of Renato, the legendary vintner who put Barolo on the map.

We have travelled to Piedmont and to the heart of Barolo country, where the principal grape, Nebbiolo, reigns. This particular vineyard is perched high on the hills, framed by the Pennine Alps mountain range that divides Italy and Switzerland to one side and, to the other, woodlands favored by seasonal truffle hunters. Ratti’s land is swathed in grapes, the native Nebbiolo along with the Dolcetto, some of which are still hanging to their vines even though it’s the end of harvest. He grabs a bunch and hands it over to me. The sweetness is intense. He points to the vineyards, now veiled in the golden light of dusk. “This is my last land. I came here on a day like this and just fell in love. It is so isolated, the views so spectacular. I knew I had to buy it.”

Pietro has plans to develop an old farmhouse on site into a guesthouse. “I want our visitors to get a sense of this place, the people, our history. The best way to know a wine is to see, touch and feel the land. Then the taste comes.” I suggest to him his role is much like an artist — creating visceral connections. He nods a few times. “The land here makes it easier to do so, but it does require effort to make great wine. From a dream to reality is a lot of hard work.”

The Ratti winery sits south of Alba in the commune of La Morra, the highest and largest village in the Barolo appellation, and responsible for 25 percent of the coveted red wine. The cool air and gentle breeze from the mountains, and temperate influence of the nearby sea create a beneficial climate for conventional viticulture. It also allows for a longer growing season, which works well for the Nebbiolo variety.

The terroir in this part of Piedmont is almost entirely dedicated to cultivating grapes for local wineries and hazelnuts for the nearby Ferraro chocolatier. Ratti has around 60 hectares (148 acres) of vineyards spread across the region on which it grows Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Timorasso, Dolcetto, Barbera and Nebbiolo, the latter comprising about 60 percent of plantings.

The Ratti winery sits in the commune of La Morra in the Barolo appellation

“This is my last land. I came here on a day like this and just fell in love. It is so isolated, the views so spectacular. I knew I had to buy it.”

A SENSE OF PLACE

Ratti’s winery and visitor center opened in 2005. The original space, built by his father in 1968, proved too small to accommodate the company’s growth and is now used as the cellar. The new building is the work of Pietro’s uncle, the architect Marco Sitia. With its clean modernist structure, flowing lines tracing the surrounding hills, and living green roof, it strikes up a convivial conversation with the landscape here.

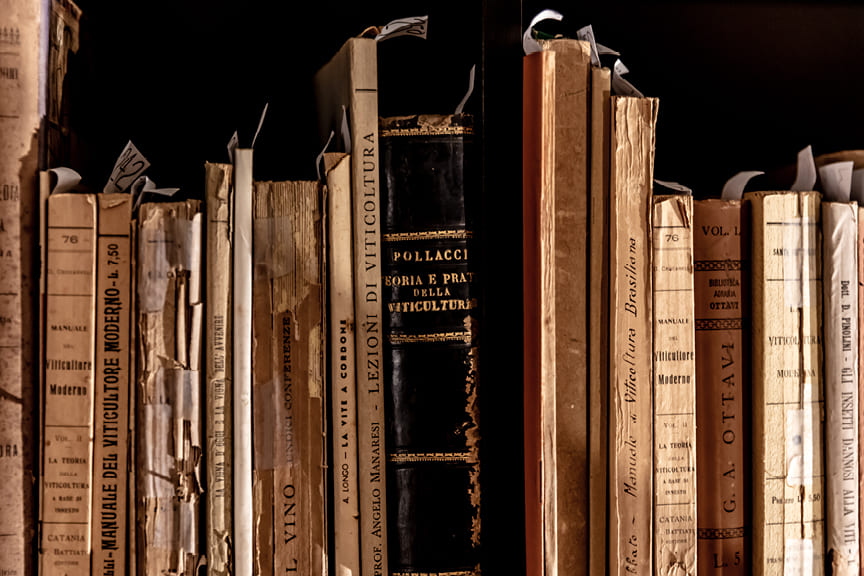

Inside is an open plan with wide windows framing vistas over the rolling vineyards. The furniture, mostly made of wood and other natural materials, are the work of Milanese designers. The complex houses the Museo Ratti with its collection of ancient viticulture and vinification artifacts. Pietro fetches a key to the library that was established by his father. The room is reserved for special guests and private tastings, for it houses more than 2,000 books on viticulture and local history. Meticulously archived, some are collectables and rare editions in French and Latin — the original language of viticulture — while others are by Renato Ratti, himself a prolific writer and illustrator. His witty drawings light up the walls of the visitor center.

It’s hushed in the library, a place where Pietro often takes refuge to write and reflect. “Our winery is connected to culture through my father,” he explains as he carefully unfolds one of the art books lying on the table. “For him, wine was more than something you drink. He was deeply interested in the culture and the life around it.” Pietro is now in the process of renovating the 13th-century Abbey of L’Annunziata (also known as Monastery of Marcenasco) to create a wine museum dedicated to the La Morra region, with plans to open to the public in June 2023.

Ratti benefits from year-round wine tourism, as the area is ideally positioned an hour’s drive from Turin and two from Milan and Genoa. The main pull is the Barolo, but visitors also come for the truffle season in mid to late fall. The Ratti guest experience is anything but commercial and accommodates no more than five to eight people to ensure a more intimate encounter. A tour of the winery and a visit to the cellars concludes in the tasting room — a generous space with floor-to-ceiling windows offering views of the hushed vineyards, and where visitors sample wines paired with food and small bites.

We leave the visitor center and walk through the cellar where post-harvest production is in full swing. Here, grapes from each plot are macerated in their individual stainless-steel tanks. At the end of the first maceration (10 to 15 days), the team tastes the wines and makes decisions about further length of time on the skins. A second skin contact can take another 20 to 30 days, making a total of 30 to 40 days maceration. He clarifies: “In the process we gain softer tannins and get more dense and complex flavors for wines that are more elegant and complex.”

The Barolo is kept in barrels for a minimum of 24 months. Ratti works with large barrels — 25 to 50 hectoliters — for Marcenasco and Rocche dell’Annunziata as they offer a more neutral environment and a slower aging process. Conca ages in smaller 225-liter French oak barrels for 12 months, followed by an extra 24 months in the larger barrel. He clarifies: “Barolo needs to get a body-power complexity for which we do a longer maceration and longer aging.”

Harvest typically happens in October. “Most of the vineyards here are Nebbiolo and in 10 years the whole area will be Nebbiolo. I call it nebbioloization,” Pietro says with a chuckle.

A team of three does the tastings. “Developing a sophisticated palate for tasting requires practice,” he continues. “Our skill is always evolving and you never feel like you’ve completely mastered it … but when you get it, then you get it.”

pietro ratti in the tasting room at the visitor center, where floor-to-ceiling windows offer vistas over the Ratti vineyards and beyond

“With its clean modernist structure, flowing lines tracing the surrounding hills, and living green roof, it strikes up a convivial conversation with the landscape”

THE RATTI LIBRARY, visitor center, cellar rooms, and historical bottles from the collection

RENATO AND THE BIRTH OF BAROLO

Renato Ratti’s family came from the Piedmont region. While studying at the renowned oenology school in Alba, he was recruited by Cinzano, the Turin vermouth company, which positioned the young Renato in Brazil. Soon after settling in his new home, he would be joined by his wife, Beatrice (“Bibi”), whom he met in Genoa shortly before he accepted the Cinzano post.

At first the couple enjoyed their time in São Paulo, where Renato became head of Cinzano’s South American operations. Though she was college educated, Bibi found the job opportunities limited and grew restless. The couple returned to Italy, where they felt job prospects for both of them would be more equitable. The year was 1965.

Once in Genoa and with plans to settle in Piedmont, Renato placed an ad in La Morra’s local paper: “I’m looking for a castle,” it read. The young winemaker always dreamed of owning a castle but those inside the wine region were out of reach. But outside the region was something he could afford, a small plot in the historic zone of Marcenasco, adjacent to the Abbey of L’Annunziata. Because monks built the ancient monastery with the intention of making wine, the surrounding land, Renato concluded, must be good for cultivating grapes. It was here where he created his first single-vineyard Marcenasco Barolo.

Bibi came from a sophisticated Genoese family. She was a city girl and reluctant to move somewhere so remote. But when Renato brought her to La Morra, she was instantly charmed. “He showed her this vineyard and she fell in love with the place,” says Pietro, pointing to a pretty plot of land by the visitor center. Over the years, Renato would purchase the surrounding vineyards, often bartering hard with local farmers who were reluctant to sell, gradually building the Ratti winery.

Much of Italy in the 1960s was rural, the wines were not stylish and the industry lacked the sophistication to make them so. “Wine was like food here; it wasn’t an intellectual drink but a simple alcoholic beverage,” explains Pietro. But his father saw an opportunity. He knew that the Nebbiolo grape and the local terroir were able to express a very different wine from place to place, even in a short distance.

Having visited Burgundy and Bordeaux and upon seeing how the appellation system worked favorably there, Renato suggested to a group of local winemakers that they take a similar approach, concentrating on quality and single-vineyard wines with a unique terroir-driven personality. Most importantly, he highlighted the significance of establishing an appellation system for Barolo.

“My father was a man of ideas but he was also pragmatic. He was a kind of messiah: people listened and followed him,” Pietro says. But, Renato ensured a democratic process. The collective discussed the rules and regulations for making Barolo, and working with a cartographer, Renato drew the map to define the appellation borders.

With two sons and a wife to support, he had to create another source of income while waiting for Barolo to age. So, Renato cultivated other varieties, such as Dolcetto, which is bottled a year after its vintage and makes easy, affordable wines that can be drunk sooner, and, thus, provide income.

Smiling, Pietro recalls his father’s ambitions. “His mind was bigger than the wines. He became a leader of the Italian wine movement. When I was a child people were calling him daily for advice. Our home was always full of interesting people, even Robert Mondavi came to visit. My father was a strong figure and everyone respected him.”

Pietro followed in his father’s footsteps, also studying at Alba’s oenology school. His plans to continue his education in social-political science in Milan were interrupted when Renato passed away. He was only 44 years old. The year was 1988 and Pietro had just turned 20. The family made a swift decision for him to run the winery alongside an older cousin who was already involved in the business. Renato had been a pragmatic man, and when he was diagnosed with cancer, he set about directing the transition. “He even wrote a book on how to do this,” Pietro recalls. When the cousin retired, Pietro bought his shares. “I remember telling my mum: let’s keep going in good and bad years. And she trusted me.”

CONTINUING A FAMILY LEGACY

Pietro has three children — the eldest is almost the same age as he was when he inherited the winery. I ask if Pietro sees his children following in his footsteps. “It’s difficult to say these days. In my time it was mandatory,” he reflects. “But who knows? To be a vintner in the ‘90s was to be a farmer; now you’re a superstar.”

He holds no regrets. “At 20, I had my own dreams, and those have come true. At the end of the day, if you have a direction, put in the effort and you work hard, you can achieve a lot — especially here. This is a land that takes a lot, but gives back a lot, like the Nebbiolo grape. We are not dreamers here. What we do takes a lot of hard work, a lot of tension.”

I ask Pietro what his father would make of Ratti’s current success and the fame Barolo wine enjoys today. “Oh, he would be happy,” he says, his voice charged with enthusiasm. “He enjoyed every minute of his short life and passed away too soon to see the development of Barolo. But I am sure he foresaw its success.”

See the Ratti collection and learn more about the winery.

an old photograph captures the young Ratti family, while pietro samples a vintage

PHOTOGRAPHY BY Leigh Banks, Helen Cathcart, Roberto Fortunato

We recommend

OUR GUIDE TO VISITING THE RATTI WINERY IN PIEDMONT

Winemaker Pietro Ratti makes elegant wines from high-elevation vineyards in La Morra in the Barolo appellation, combining depth with distinct elegance. Complete your visit with a stay at the winery and a tasting with Pietro and his team

WINE TRAILS OF THE LANGHE AND ROERO

Commencing our Italian road trip in the Langhe and Roero in Piedmont, where we visit the wineries and sample the cuisines that express this unique place

EXPLORE MAZE ROW’S HALO WINES

Maze Row has curated a collection of wines from unique producers, each with their own individual expression. Sommelier and Italian wine specialist John Irwin picks out the halos in the company portfolio

AN AMERICAN IN PIEDMONT

Chris Bangle, the American designer famed for his work at Fiat and BMW, reveals his favorite places to eat, sleep, drink and visit in and around Turin and Piedmont